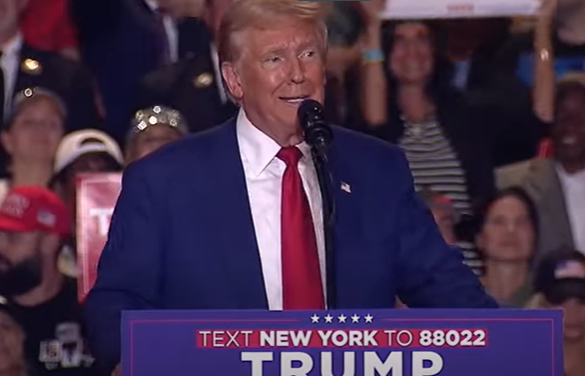

In all this ongoing discussion about Donald Trump’s pitiful lack of fitness for office, we feel compelled to make a critical point, and that is, he’s too wimpy to serve as president of the United States. We’re too tough as a people and our responsibilities too hardy, to listen to a whiny guy talk about himself at a microphone and pretend this doesn’t clash dreadfully. Certainly, not every American leader is going to be Abraham Lincoln and demonstrate an almost superhuman capacity to preserve and to protect the union. But we don’t need someone whose nursed personal grievances have the effect of a miserable old guy jumping up and down on a fragile fault line, in an attempt to roil a national-sized temper tantrum.

Look, I get it. It’s difficult, even after 159 years, for some people to come to grips with the fact that the Confederacy lost the Civil War. Their hatred of the United States Federal Government runs so deep, that they would even embrace a flailing New York industrialist TV show personality because his message of anarchy resonates directly and vividly. They compress his mental and physical duress as an unprepared and childlike 78-year-old, with their own hopes for the country, which is the disintegration of the country to a pre-1865 condition. In short, the most rabid base of Trump’s support senses a willing participant in the fracturing and dematerialization of America.

This is not in the slightest to discount the real and thorny challenge of the union itself, western civilization’s most vital expression of that balancing act struck between the many and the one. From the beginning of our national history, we have struggled with the extraordinary tension of states’ rights versus a strong central government, going back to that seminal argument between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

Critically, without discounting those many real and granular differences, Lincoln understood the sin of slavery and the value of preserving the union without this sin, as opposed to surrendering the country to facilitate a single region’s societal affliction. In the intervening years, many more have died to fulfil what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. identified as the nation’s oath to live up to its own creed. Leaders suffered consequences, either changing parties to ride the times, or abandoning their own hopes of running in recognition of their own political untenability. When President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination, he believed he simultaneously eliminated his own chance at successful reelection. The Texan surmised that the stronger federal codification of civil rights crippled him at the heart of his base. The backlash to the feds enforcing the desegregation of the Alabama Public School System prompted Governor George Wallace – who stood in the schoolhouse door of the state university to prevent the enrollment of African American students – to unsuccessfully run for president on a platform of segregation. Wallace sought to coalesce and galvanize the very base that Johnson refused to placate in the 1968 Democratic Primary.

Vote-harvesting politicians in the South or the vicinity of the South have since continued to pander to how they perceive or misperceive voters – even white supremacist voters. When he launched his 1980 presidential bid, for example, Ronald Reagan, went to Neshoba County, infamous scene of the murders of Civil Rights workers, to make a case for how, in his words, “we’ve distorted the balance of our government today by giving powers that were never intended in the constitution to that federal establishment.” Running for president in the 1980s and 1990s, Joe Biden – trying to pivot from his liberal record – mangled a message about the supposed benefits of coming from Delaware, “a slave state.” To be clear, this pandering doesn’t always contain a nefarious undercurrent. Derided as the scion of a Connecticut political family, George W. Bush in his Texas gubernatorial bid repackaged himself as a brush-clearing, armadillo-wrassling good ol’ boy, a persona maintained even as he expanded to the national level as a “compassionate conservative.”

Regardless of how these other politicians met the challenge of the enormity of the country itself, failing to project adequate largess of authentic spirit on par with riverboat lawyer Lincoln – but then who would – and the perceived agonies ongoing in one specific place, nowhere have we seen a politician placate the tiniest worst of ourselves on that scale we see with Trump. This is the danger in our complicated country of coddling a fragile egomaniacal celebrity. He thrives on being loved and admired, and when he doesn’t feel loved, he goes to whatever group gives him love, indulging therein an insular cultlike fantasy, which back on a bigger, real-sized national stage finds him jarringly incoherently ranting in the littlest, meanest language imaginable, about Haitian immigrants “eating cats and dogs.”

We understand the fundamental exhilarating principle of our sprawling country, namely that part of the Constitution’s delicate and sacred balancing act necessitates the constantly urgent interpretation and lawful application of how individuals interact with one another, and with government, and how states interact with the whole, and that what fits one place in a certain case may not have uniform application elsewhere. But Lincoln recognized that in one area in particular, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” We don’t discount the real-time collisions of Hamilton and Jefferson in the maintenance of federal and state government, vitally, in the preservation of liberty within the crucial context of public safety. Indeed, American leaders who expand beyond the boundaries of states in an attempt to encompass the country must possess a special sophistication and finally, extraordinary strength. But then, that’s precisely the point.

Trump’s candidacy regrettably represents the near perfect collision of grievances that go back at least to 1865 (and further of course, but there as they pertain to the tragedy of civil war) and a weak-minded individual in need of attention. Finally, it shows Trump’s willingness to become a tool of that aggrieved, and at its ugliest (witness Charlottesville and the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021) seditionary spirit in a terrifyingly small part of the country. Trump represents the essence of weak leadership in a powerful country with a complex and sacred history, built on the sacrifices of tough people. It’s not just that he incessantly whines, which would be bad enough, it’s that he whines for attention to those still too weak to surmount that most fundamental challenge put to us by Lincoln and then by King, of truly living up to the – at times – difficulty of the e pluribus unum American Dream. Years ago, a Time Magazine article showed George Herbert Walker Bush on a family yacht against the backdrop of the unfolding 1988 presidential election. The accompanying magazine headline read, “Fighting the Wimp Factor,” as if a hero who fought for his country in WWII and served – whether you agree with him or not on the issues – had something to prove. Applied to the late elder Bush, the headline was offensive then and now. But it somewhat more accurately reflects Trump, except that Trump doesn’t fight the wimp factor. Up against his own withering, victimized and self-pitying condition, he caves into it completely, and those still stinging from a fight with the federal government undertaken in defense of our collective freedom, welcome him as the hero he dreams himself to be.

(Visited 42 times, 52 visits today)

As the 2020 presidential election approaches, the question of whether Donald Trump is fit for the U.S. presidency continues to be a topic of debate. Insider NJ recently examined his leadership style to determine if he is the right person to lead the country for another four years.

One of the key aspects of Trump’s leadership style is his unorthodox approach to governance. Unlike traditional politicians, Trump has a tendency to speak his mind and make decisions based on his gut instincts rather than relying on expert advice or established protocols. While some see this as a refreshing change from the status quo, others worry that it could lead to impulsive and potentially dangerous actions.

Another hallmark of Trump’s leadership style is his confrontational and divisive rhetoric. Throughout his presidency, Trump has frequently used inflammatory language to attack his opponents and stoke division among the American people. While this approach has energized his base, it has also alienated many moderate voters and exacerbated political polarization in the country.

On the policy front, Trump has pursued a number of controversial initiatives, such as rolling back environmental regulations, implementing strict immigration policies, and renegotiating trade deals. While some of these actions have been popular with his supporters, others have been met with criticism and legal challenges.

In terms of crisis management, Trump’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been a point of contention. Critics argue that his initial downplaying of the virus and inconsistent messaging have contributed to the severity of the outbreak in the United States. Proponents, on the other hand, point to his efforts to ramp up testing and secure medical supplies as evidence of effective leadership during a challenging time.

Ultimately, whether or not Donald Trump is fit for the U.S. presidency is a subjective question that depends on one’s political beliefs and values. While some may appreciate his unconventional approach and willingness to shake up the establishment, others may view his leadership style as reckless and divisive. As voters head to the polls in November, they will have to weigh these factors and decide for themselves if Trump deserves another term in office.