A bifurcated establishment tried to choke down the news this morning that the party organization lines as we know them – presided over by Frank Hagues in training, walking around like kings and queens of fortified small-time kingdoms, may wash out to sea by the end of the week like so many plastic shoveled sandcastles.

Part of that establishment sides with state Attorney General Matt Platkin in his opinion that the lines should go, and why try to jump in front of a speeding train carrying the cattle cars of the 49 other states. But then, another wing wants to move to intervene, should Judge Zahid N. Quraishi overturn the three state statutes that prescribe how New Jersey designs its primary ballots. There was some bitter Benedict Arnold talk in those circles, pertaining to Platkin and how Governor Phil Murphy “made him,” and therefore, presumably, the AG should have refrained from opining “against Phil,” and allowed the parapets of county party organizations to “make” First Lady Tammy Murphy the next United States senator from New Jersey.

“I mean, how dare he,” an insider seethed.

Within that group, party leaders prepared to counteract the expected decision by Quraishi, to protect the lines as they now exist. Amid the early champagne bottle shaking among Kim backers and progressives, older regime establishment Dems growled about how those neophytes won’t know what to do without “real organizations” behind them.

At least a handful of them cited as legal precedent Quaremba v. Allan, a case decided by the New Jersey Supreme Court on March 13, 1975.

In that case, the plaintiffs challenged as unconstitutional the provisions of N.J.S.A. 19:49-2 which regulate the positioning on the lines of a voting machine of the names of candidates for nomination at a primary election. They contended that even though N.J.S.A. 19:23-24 expressly excepts from its provisions “counties where section 19:49-2 of the Revised Statutes applies,” still the county clerk of such county should and must comply with the provisions of N.J.S.A. 19:23-24 and list all candidates for nomination to any given office, in the order determined by lot, in a single column or row. Finally, they asserted that although defendant County Clerk of Bergen County purported to follow the provisions of N.J.S.A. 19:49-2, in fact he abused his discretion and discriminated against candidates such as plaintiffs who are not affiliated with the Bergen County Republican organization.

They lost.

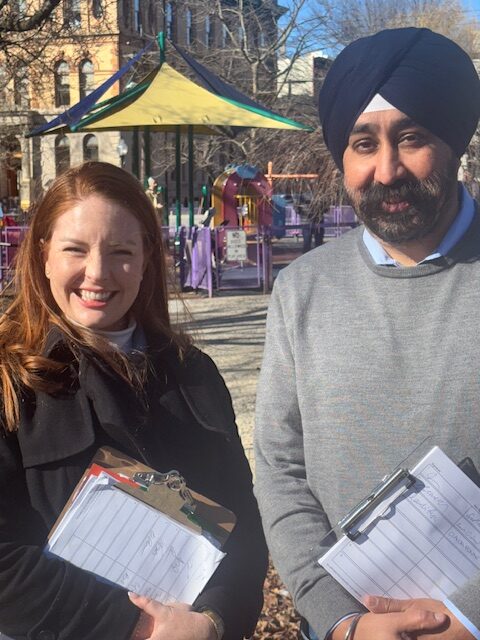

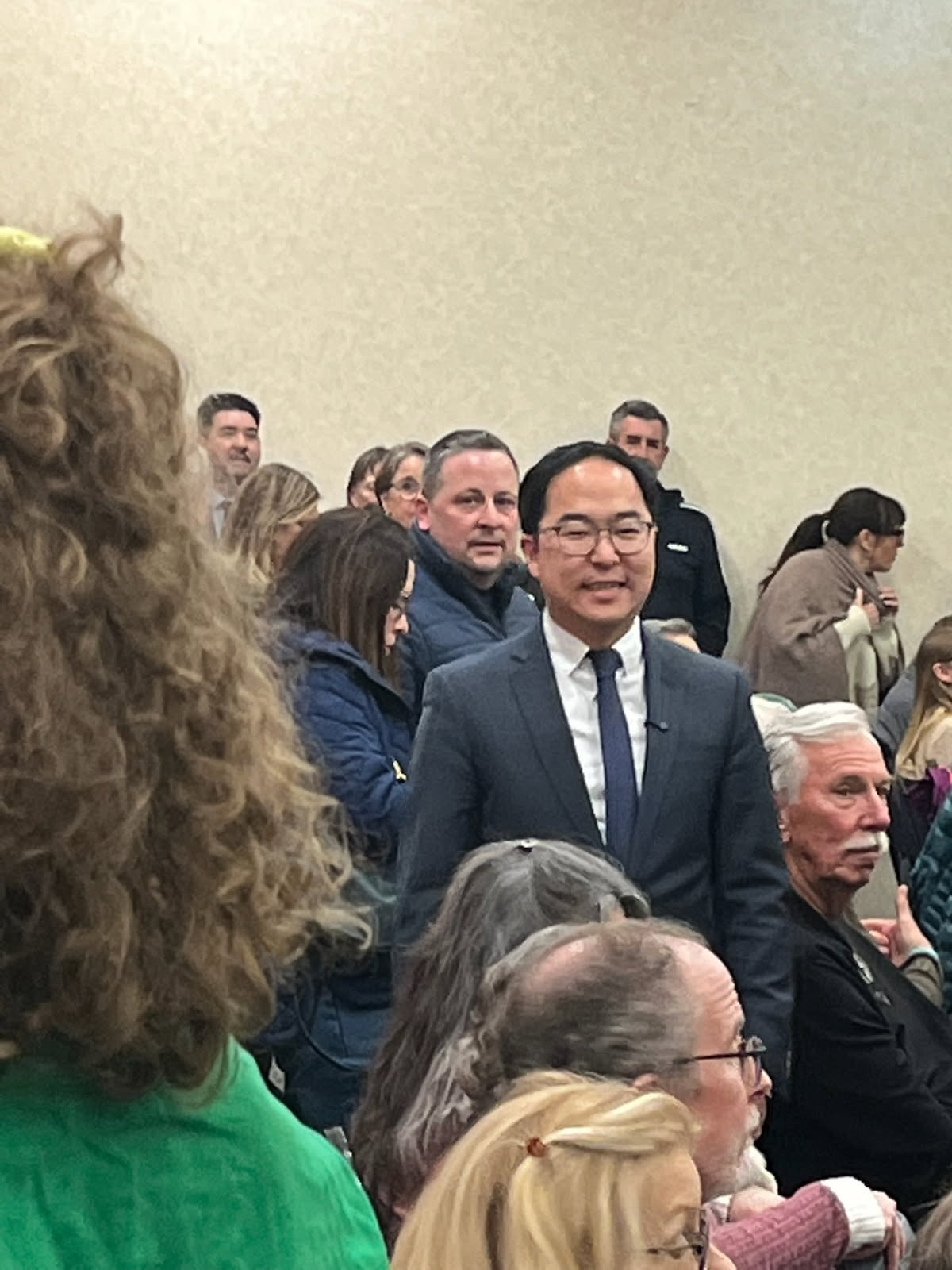

Now, the federal court is examining a lawsuit filed by U.S. Rep. Andy Kim, running in the Democratic Primary for the United States Senate against First Lady Murphy. Kim argues that New Jersey ballot design helps candidates endorsed by county political leaders by putting them in favorable positions. The Quaremba v. Allan case supplies a different take, namely that eliminating bracketing around common aims or principles, whatever the effect on an unaffiliated candidate, does not necessarily better serve the public interest.

Here’s a breakdown of the key arguments in the Quaremba case leading to that end, according to the court –

“In this case plaintiffs charged defendant with intentional and purposeful discrimination against non-organization candidates. However, as the trial court found and as the Appellate Division agreed, the evidence adduced did not furnish adequate support either for the charge of intentional discrimination or for plaintiffs’ challenge to the good faith of defendant county clerk. Adequate basis for such charges is not to be found in plaintiffs’ criticism of several of the 517 different forms of ballot defendant was called upon to prepare for the primary election. (The differing forms of ballot were required because not all candidates were to be voted for throughout the county; some were to be voted for only in one district or one municipality.)

“Aside from the charge of intentional discrimination, plaintiffs’ principal criticism was of the county clerk’s refusal to structure the ballot in the form of a single column with the names of the candidates for each office, affiliated and non-affiliated, following each other in the sequence determined by a drawing and these in turn followed by a similar listing of candidates for the next office and so on.

“Under that proposal, the names of those who had filed a joint petition for different offices and those who had affiliated with them, although appearing in a single column, would be separated from each other by the names of unaffiliated candidates seeking the same offices.

“There is no merit to plaintiffs’ contention that the ballots should be structured as they suggest. Indeed such a separation of the names of those affiliated candidates unless they consent thereto would be contrary to the legislative *17 purpose evident in N.J.S.A. 19:49-2. Harrison v. Jones, supra, at 44 N.J. Super. 461.

“Nor is it an abuse of discretion for a county clerk to accord affiliated candidates a line of their own. ‘On the contrary he should [place them on a line of their own] if that course is feasible and if in the context of the whole ballot it would afford all the voters a clearer opportunity to find the candidates of their choice.’ Richardson v. Caputo, supra, 46 N.J. at 8; see also Farrington v. Falcey, supra, 96 N.J. Super. at 413-414. In such case, the assigned line should normally be exclusively that of the affiliated candidates. Unless space requirements dictate otherwise, unaffiliated candidates for the same or other offices should not be added to the line allocated to the affiliated candidates.

“As we have noted, N.J.S.A. 19:49-2 does not mandate a drawing when there are no competing groups and only unaffiliated candidates. Bado v. Gilfert, supra. However, to eliminate any suggestion of favoritism, a proper exercise of the county clerk’s discretion in that situation should normally call for a drawing among the unaffiliated candidates for each office and the listing of their names in a single column in the order determined by the drawing.

“The same course normally should be followed as between unaffiliated candidates for a particular office without, of course, affecting the inclusion of the affiliated candidate for that office with his group. Cf. Moskowitz v. Grogan, supra, 101 N.J. Super. at 116.

“Finally, unless impossible because of the physical limitations of the voting machine at a particular primary election, the county clerk must ‘give effect on the ballot to a consensual arrangement whereby all of the candidates at a given level agree to run on a line of their own for any given office with no other candidate * * *.’ [Alaimo v. Burdge, 63 N.J. 574, 575 (1973)].

On Monday, players in party organizations readying their cause to counteract the coming decision later this week, admitted the Kim case had somewhat blindsided them. Armed with Quaremba v. Allan, “We’re going to get our ducks in a row here,” one source assured InsiderNJ, and hit back in as large an organized body of interested establishment parties once Quraishi goes where they believe he will go by week’s end.

(Visited 55 times, 59 visits today)

In the recent case of Quaremba v. Allan, a New Jersey court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, Quaremba, in a dispute over ownership of a valuable piece of property. The case centered around allegations of fraud and misrepresentation on the part of the defendant, Allan, who had allegedly misled Quaremba into signing over the property to him under false pretenses.

The court found that Allan had indeed engaged in fraudulent behavior and had knowingly deceived Quaremba in order to gain control of the property. As a result, the court awarded damages to Quaremba and ordered Allan to return the property to its rightful owner.

The Empire, a prominent real estate development company, was also implicated in the case as they had been working with Allan on the development of the property. The Empire’s response to the ruling was swift and decisive, with the company publicly denouncing Allan’s actions and announcing that they would no longer be working with him on any future projects.

The Empire also issued a statement expressing their commitment to ethical business practices and their dedication to upholding the highest standards of integrity in all of their dealings. The company emphasized that they would be conducting a thorough review of their partnership with Allan and taking steps to ensure that similar incidents did not occur in the future.

Overall, the Quaremba v. Allan case serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of honesty and transparency in business dealings. It highlights the potential consequences of engaging in fraudulent behavior and the need for companies to carefully vet their partners and associates to avoid being implicated in unethical practices.

In conclusion, the Empire’s response to the case demonstrates their commitment to ethical business practices and their willingness to take swift action in response to wrongdoing. It also serves as a reminder to all companies to conduct themselves with integrity and honesty in order to maintain their reputation and avoid legal repercussions.